This may not answer your question directly, but is related:

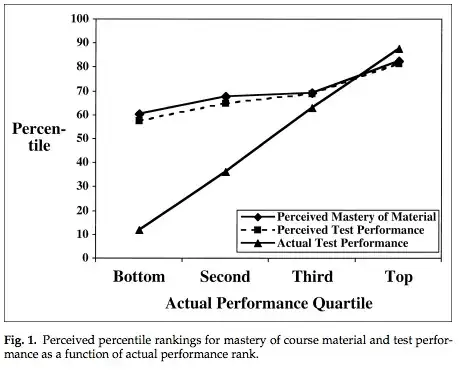

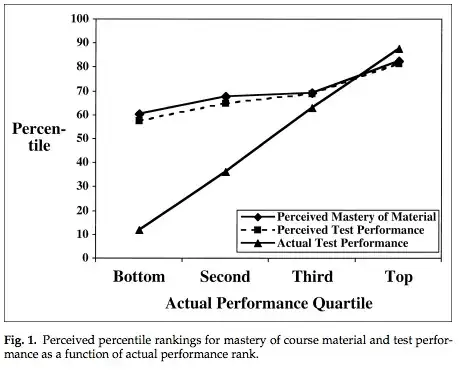

Kruger and Dunning (1999) conducted a study in which people performed a variety of 'tests' in different domains, such as logical reasoning, grammar, and humor. After taking a test, participants were asked to judge their performance relative to other test-takers, and to estimate their objective score on the test (how many questions were answered correctly).

What they found was that the subjects who performed the worst actually overestimated their performance the most. If you take their performance estimate as a proxy for confidence, then it supports your hypothesis-- but only to a relative degree. That is to say, participants who performed poorly did not estimate their ability to be better than good performers and vice versa; however, those who performed the worst were more confident in their ability. It's a bit confusing, and D&K can explain it better-- there's actually a paragraph in their article (second to last) which relates their findings to work on overconfidence.

The explanation that Kruger and Dunning give for this effect is that the metacognitive ability to assess one's performance is a correlated with actual performance on the same task. Thus, somewhat paradoxically, those who perform poorly may be unaware of their poor performance, due to their inability to predict how well they did.

Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: How

difficulties in recognizing one's own incompetence lead to inflated

self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77,

1121-1134.