From p. 207 of Geoffrey Miller (2001). The mating mind: how sexual choice shaped the evolution of human nature. Anchor Books. ISBN 0-385-49517-X

In our research on mate search strategies, colleague Peter

Todd and I found that a rule we call "Try a Dozen" performs as

well as the 37 percent rule under a wide range of conditions. Try

a Dozen is simple: interview a dozen possible mates, remember

the best of them, and then pick the very next prospect who is

even more attractive. You do not have to estimate the total

number of potential mates you will encounter in your

reproductive lifetime; you only have to bet that you will meet at

least fifty or so. Humans seem to follow something like the Try a

Dozen rule: we get to know a number of opposite-sex friends

during adolescence, fall in love at least once, remember that

loved one very clearly, and tend to marry the next person who

seems even more attractive. Each individual is "satisficing"-

looking for someone who is pretty good and good enough, rather

than the absolute best they could possibly find. But at the

evolutionary level, these satisficing rules impose sexual selection

that is almost as strong as the most complicated, perfectionist

decision strategy.

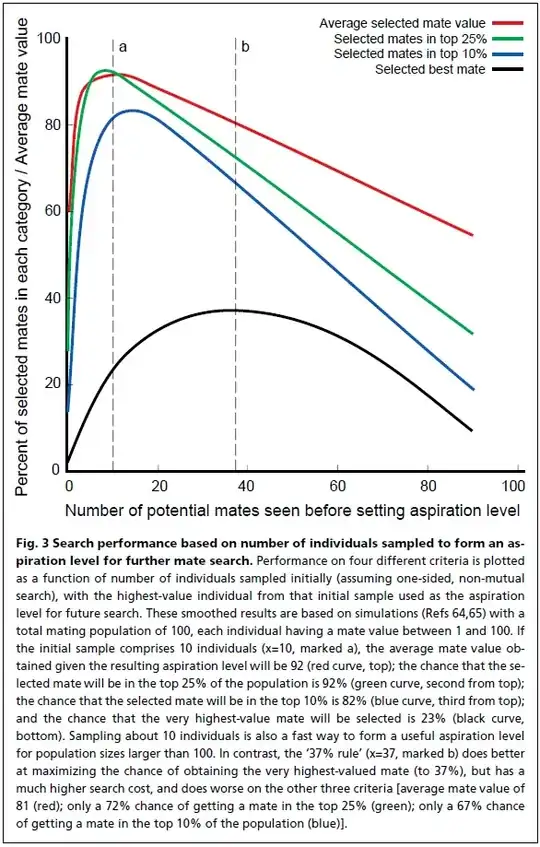

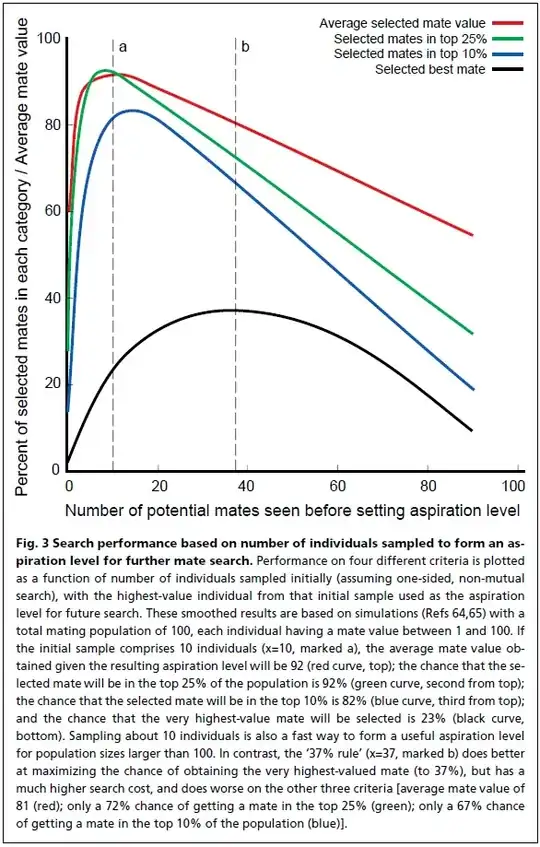

I also turned up a 1998 review by Miller and Todd "Mate Choice Turn Cognitive", which does get to mating strategies in its final pages, best summarized by:

By sampling a much smaller number of

prospects initially, say a dozen, one can actually attain a

higher expected mate value than the 37% rule delivers (although

a lower chance of finding the very highest-valued

prospect), with much lower search costs and a much lower

risk of being stuck with a low-value mate[64,65] (Fig. 3).

More importantly, the ‘secretary problem’ ignores the

problem that a prospect you desire may reject you. This

mutual choice constraint makes the search much harder[64,65].

Game-theory models of ‘two-sided matching’ address these

complexities[61] directly, and propose various search strategies

which guarantee that a population reaches a ‘stable matching’:

a pairwise assortment of individuals where no individual

would prefer to be mated with someone else who would also

prefer to be mated with them. However, two-sided matching

models typically assume strict monogamy (no ‘extra-pair

copulations’), complete information and exhaustive preferences:

everyone has complete, consistent, transitive

preferences across all possible prospects that they encounter.

- Roth, A.E. and Sotomayor, M.A.O. (1990) Two-sided Matching: a Study

in Game-theoretic Modeling and Analysis, Cambridge University Press

- Todd, P.M. (1997) Searching for the next best mate, in Simulating

Social Phenomena (Conte, R., Hegselmann, R. and Terna, P., eds),

pp. 419–436, Springer-Verlag

- Todd, P.M. and Miller, G.F. Heuristics for mate search, in Simple

Heuristics that Make us Smart (Gigerenzer, G., Todd, P.M. and the ABC

Research Group), Oxford University Press (in press)

So yeah, the problem is not that simple (as optimal stopping) if one considers mating a game (in the sense of game theory). I haven't yet looked at the latter line of research... but it's a whole book. The idea seems centered on the stable marriage problem. An optimal algorithm also involves a number of rounds, with rejection and "maybe" answers; from Wikipedia:

- In the first round, first a) each unengaged man proposes to the woman he prefers most, and then b) each woman replies "maybe" to her suitor she most prefers and "no" to all other suitors. She is then provisionally "engaged" to the suitor she most prefers so far, and that suitor is likewise provisionally engaged to her.

- In each subsequent round, first a) each unengaged man proposes to the most-preferred woman to whom he has not yet proposed (regardless of whether the woman is already engaged), and then b) each woman replies "maybe" if she is currently not engaged or if she prefers this guy over her current provisional partner (in this case, she rejects her current provisional partner who becomes unengaged). The provisional nature of engagements preserves the right of an already-engaged woman to "trade up" (and, in the process, to "jilt" her until-then partner).

- This process is repeated until everyone is engaged.

So, Miller and Todd cleary don't think this stable marriage problem is too relevant for reality. Unfortunately, by the time of their review (which is now two decades old), there's wasn't much else proposed that was taking into account the mutual-choice aspect of mating and the "satisficing" nature of human choice in general (that Miller and Todd favor).