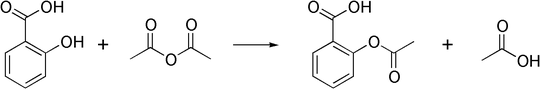

But I don't understand why - shouldn't more protons in the environment lead to faster protonation of the carbonyl oxygen of acetic anhydride? Could you please explain it to me?

The short answer is "side reactions". Without more information about your exact experimental conditions, or even better, data about the obtained yields of the desired product and of byproducts, it isn't possible to explain conclusively what went wrong, but here are some ideas.

Acetyl sulfate formation. In the comments you you implied that you used anhydrous sulfuric acid. Under those conditions, acetic anhydride can undergo solvolysis to yield acetyl sulfate and water. $$\ce{CH3COOOCCH3 + 2H2SO4 <=> 2 CH3COOSO3H + H2O} $$ Acetyl sulfate might be a less active acetyl transfer reagent than acetic anhydride, or the water formed may hydrolyze some of the acetic anhydride or even the formed acetyl sulfate.

Dehydration/sulfation of the starting material instead of acetyl transfer. If you really did use anhydrous sulfuric acid, it is a powerful dehydrating reagent. It could be possible that you are sulfating the alcohol or even the acid group (or both?) of the substrate, forming either o-sulfoxybenzoic acid (sulfation at $\ce{-OH}$ group) or sulfosalicylic acid (sulfation at $\ce{-COOH}$ group).

The heat of mixing of concentrated sulfuric acid with water is about $-74~\mathrm{kJ~mol^{-1}}$, judging from Figure 34b of a NIST treatise on the subject. The heat of reaction for hydrolysis of acetic anhydride is only $-41~\mathrm{kJ~mol^{-1}}$. Thus under anhydrous conditions, I think sulfated products will be more thermodynamically favored than acetylated products. Sulfated products will be far more soluble in water or sulfuric acid than would be acetylated products.

I would think that using more water in the reaction would help. The reason is that the heat of mixing of sulfuric acid is a very strong function of water concentration, but the heat of hydrolysis of acetic anhydride is not. So raising the concentration of water a little bit will disfavor sulfation significantly by lowering the heat of mixing of sulfuric acid, but will leave the heat of hydrolysis of acetic anhydride the same. It's worth noting that this argument is purely thermodynamic, not kinetic. But I don't think sulfation reactions are kinetically hindered under ambient conditions, so although it isn't always true, I think thermodynamic arguments are valid in this case.