Why is the molar enthalpy of vaporization of a substance larger than its molar enthalpy of fusion (at constant pressure); for example, in the case of ice and water.

4 Answers

Enthalpies of phase changes are fundamentally connected to the electrostatic potential energies between molecules. The first thing you need to know is:

There is an attractive force between all molecules at long(ish) distances, and a repelling force at short distances.

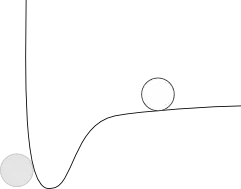

If you make a graph of potential energy vs. distance between two molecules, it will look something like this:

Here the y-axis represents electrostatic potential energy, the x-axis is radial separation (distance between the centers), and the spheres are "molecules."

Since this is a potential energy curve, you can imagine the system as if it were the surface of the earth, and gravity was the potential. In other words, the white molecule "wants" to roll down the valley until it sits next to the gray molecule. If it were any closer than just touching, it would have to climb up another very steep hill. If you try to pull them away, again you have to climb a hill (although it isn't as tall or steep). The result is that unless there is enough kinetic energy for the molecules to move apart, they tend to stick together.

Now, the potential energy function between any two types of molecules will be different, but it will always have the same basic shape. What will change is the "steepness," width, and depth of the valley (or "potential energy well"), and the slope of the infinitely long "hill" to the right of the well.

Since we are talking about relative enthalpies of fusion and vaporization for a given system, we don't have to worry about how this changes for different molecules. We just have to think about what it means to vaporize or melt something, in the context of the spatial separation or relativity of molecules, and how that relates to the shape of this surface.

First let's think about what happens when you add heat to a system of molecules (positive enthalpy change). Heat is a transfer of thermal energy between a hot substance and a cold one. It is defined by a change in temperature, which means that when you add heat to something, its temperature increases (this might be common sense, but in thermodynamics it is important to be very specific). The main thing we need to know about this is:

Temperature is a measure of the average kinetic energy of all molecules in a system

In other words, as the temperature increases, the average kinetic energy (the speed) of the molecules increases.

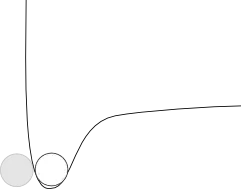

Let's go back to the potential energy diagram between two molecules. You know that energy is conserved, and so ignoring losses due to friction (there won't be any for molecules) the potential energy that can be gained by a particle is equal to the kinetic energy it started with. In other words, if the particle is at the bottom of the well and has no kinetic energy, it is not going anywhere:

If it literally has no kinetic energy, we are at absolute zero, and this is an ideal crystal (a solid). Real substances in the real world always have some thermal energy, so the molecules are always sort of "wiggling" around at the bottom of their potential energy wells, even in a solid material.

The question is, how much kinetic energy do you need to melt the material?

In a liquid, molecules are free to move but stay close together

This means you need enough energy to let the molecules climb up the well at least a little bit, so that they can slide around each other.

If we draw a "liquid" line approximating how much energy that would take, it might look something like this:

The red line shows the average kinetic energy needed for the particles to pull apart just a little - enough that they can "slide" around each other - but not so much that there is any significant space between them. The height of this line compared to the bottom of the well (times Avogadro's number) is the enthalpy of fusion.

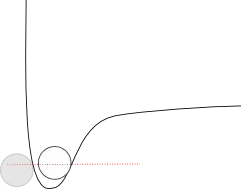

What if we want to vaporize the substance?

In a gas, the molecules are free to move and are very far apart

As the kinetic energy increases, eventually there is enough that the molecules can actually fly apart (their radial separation can approach infinity). That line might look something like this:

I have drawn the line a little bit shy of the "zero" point - where the average molecule would get to infinite distance - because kinetic energies follow a statistical distribution, which means that some are higher than average, some are lower, and right around this point is where enough molecules would be able to vaporize that we would call it a phase transition. Depending on the particular substance, the line might be higher or lower.

In any case, the height of this line compared to the blue line (times Avogadro's number) is the enthalpy of vaporization.

As you can see, it's a lot higher up. The reason is that for melting, the molecules just need enough energy to "slide" around each other, while for vaporization, they need enough energy to completely escape the well. This means that the enthalpy of vaporization is always going to be higher than the enthalpy of fusion.

- 10,430

- 33

- 62

-

Sounds great, but how does it explain the latent heat? Where is the liquid at boiling point on your energy diagram? It seems to have a shallower slope at the right hand end, which would suggest that the heat of vaporisation should be less than the heat of fusion? – alexigirl Apr 03 '22 at 23:35

-

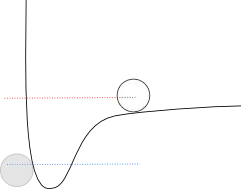

@alexigirl The red line on the second image represents the liquid at or near the boiling point. The heat of vaporization is the difference between the red and blue lines. The blue line is the liquid at the melting point. The heat of fusion is the difference between the blue line and some line (not pictured) close to the bottom of the well. – thomij Apr 05 '22 at 15:40

-

If the red line represents the liquid at or near the boiling point, it already has the energy represented by the difference between the red and blue lines. From the graph it would seem that this is enough energy to vaporise the liquid, but we know that this does not happen, we have to keep adding thermal energy for the liquid to vaporise (that would be crazy if once you had heated a pan of water to boiling point it all instantly vaporised). This extra energy is the latent heat of vaporisation. Maybe your red line is too high? – alexigirl Apr 07 '22 at 23:54

-

@alexigirl I think there still must be some confusion here. Enthalpies of phase change are differences in energy. The enthalpy of vaporization doesn't contain the enthalpy of fusion, it's the energy difference between states where the molecules are mobile but still in close proximity, and the state in which the molecules are completely unbound. – thomij Apr 09 '22 at 01:14

-

there is definitely still confusion here. You seem to be saying that the red line represents the energy of the liquid state at or near the boiling point, where molecules are mobile but still in close proximity. So the latent heat of vaporisation cannot include the energy difference between the red line and the blue line, because at both these lines the substance is liquid. – alexigirl Apr 20 '22 at 16:09

-

@alexigirl These diagrams represent the potential energy between a pair of molecules. For a single pair, the energy needed to melt is the difference between zero and the blue line. The energy needed to vaporize is the difference between the red and blue lines. At the boiling point, most of the pairs of atoms will have enough kinetic energy to reach the red line, which gives them enough separation that they can escape the liquid. – thomij Apr 20 '22 at 19:17

-

So why don't they all escape then? I can heat my kettle to boiling point. But if I then switch it off, most of the water (which was at 100 degrees) does not vaporise. – alexigirl Apr 22 '22 at 00:03

-

And if, at the boiling point, the pairs of molecules have enough energy to escape, ie they are already at the red line, why should I include the energy increase between the blue and the red line, which they already possess before they reach the boiling point, in the latent heat of vaporisation? The definition I have learnt of latent heat of vaporisation is the energy required to change the state from liquid to gas at the boiling point. – alexigirl Apr 22 '22 at 00:08

-

They will all escape if you wait long enough at that temperature. They'll all escape eventually if you wait long enough at lower temperatures too - that's why liquids evaporate. Your definition of latent heat is correct, but it applies to the bulk material. In this answer I was explaining how the potential energy between single pairs of molecules leads to the latent heats. There is a link in my answer to an article about Maxwell-Boltzmann distributions that might help you understand how this works. I don't think I will be able to adequately explain it in comments. – thomij Apr 23 '22 at 13:07

-

Understood. I was confusing enthalpy of vaporisation with latent heat of vaporisation. – alexigirl Apr 25 '22 at 16:15

-

Those are two different names for the same thing. The idea in both cases is that it's the additional energy required to change a bulk substance in the liquid state at the boiling temperature to a gas at the same temperature. – thomij Apr 25 '22 at 18:56

-

Ive looked up the article on Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution thanks. From this I understand that the molecules will have a range of speeds, with the peak frequency at the lower end of the speed range. So I can see that quite a few of the molecules will be at or close to the lower line. But there will also be some near the top line. So why do you multiply by Avogadro's number? why not take the distribution of energies into account? – alexigirl Jun 07 '22 at 20:47

-

@alexigirl For enthalpy of vaporization, it's the energy required to vaporize the entire substance - in other words, all of the molecules need to move up to that line. That's why the total is given by Avogadro's number times the difference in energies. It's basically saying that every pair of molecules needs to be pulled apart. When looking at something like vapor pressure, you would take the distribution into account - this idea forms the basis of a lot of kinetic theories, from phase change thermodynamics to reaction kinetics. – thomij Jun 09 '22 at 02:57

The molar heat of vaporization is greater than that of molar heat of fusion due to the larger amount of energy required to break the strong attractive forces that exist between molecules of liquids than that of the attractive forces in molecules of gases.

-

Welcome to Chemistry.SE! Anyone is welcome to contribute answers but the aim of this site is quality and usefulness to future users (essentially we aren't Yahoo Answers). Please take a minute to look over the help center to better understand our guidelines and question policies. – A.K. Aug 14 '18 at 20:20

-

1You should try to answer why the forces are stronger too otherwise the answer is really incomplete. – A.K. Aug 14 '18 at 20:22

Ice is less dense than water, that's why ice floats on water. The lower density of ice means that the average distance between water molecules in ice is greater than the average distance between water molecules in the liquid state. Because of the greater distance between water molecules in the solid compared to the liquid, molecule - molecule interactions (such as van der Waals and dipole interactions, as well as hydrogen bonding) will be less in the solid than the liquid. So while we need to put energy into ice to disrupt the lattice structure and break the attractive interactions, this energy is offset to some degree by the even stronger attractive forces that exist in the liquid, since the attractive forces are actually greater in the liquid than the solid.

In the gas phase the molecules are far enough apart that attractive forces between molecules are minimal. Therefor, when we go from liquid to gas we must put in a lot of energy to break all of the strong attractive forces that exist in the liquid without any offset because of the lack of significant attractive forces in the gas.

- 84,691

- 13

- 231

- 320

Enthalpy is state function which is defined as $H = U + pV$, it includes internal energy of the system and energy to create the system volume (boundary work).

Internal energy may be decomposed in several terms: oscillation around a equilibrium centre, vibrational states (stretching and bending). Generally speaking (there might be counter example for some exotic material or at temperature close to $0\ \mathrm{K}$), internal energy increase with temperature because the partition of accessible vibrational states increases (higher states activate with temperature).

About the $pV$ term, you first must consider that it cannot be negative. Therefore $H \geq U$. Now you just have to consider that, generally, $\Delta V_\mathrm{fus} < \Delta V_\mathrm{vap}$. For a given amount of matter, volume difference when melting is small before volume difference when vaporizing. This inequality holds, even for water where $\Delta V_\mathrm{fus} < 0$.

Combining those two arguments, you can explain why enthalpy of vaporization is many order of magnitude higher than enthalpy of fusion.

- 928

- 4

- 19