A watt is a Newton-meter per second, so testing accuracy requires only that you be able to impose a known force or load over a known distance in a known amount of time. That said, different power meter designs measure load in different ways so you may have to use different specific procedures to do this.

Accordingly, there is a short answer to your question that applies to most common situations, and a much longer answer that applies more generally.

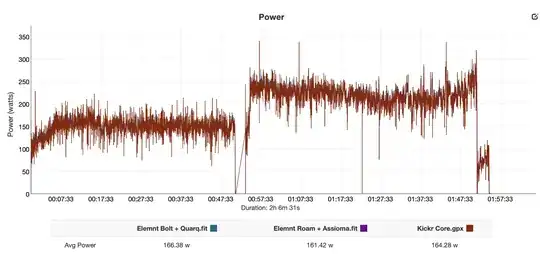

Also, as alluded to in a different but related bicycles.stackexchange question "When does power meter accuracy matter?", not every use for power requires the same accuracy or data fidelity. If your data fidelity needs are not very strict, checking your power meter is simpler and easier.

The short answer: the static load test

Most common power meters today use strain gauges (or strain gages) to measure load, and they all have the ability to report torque in Newton-meters to compatible head units (some older, now rare, power meters reported in foot-pounds but the procedure here is the same; you just need to convert from Newton-meters to foot-pounds).

For strain gage devices, weigh some barbell weights, perhaps 20 or 30 kg worth, on a good quality bathroom scale; if you don’t have one, you can take them to a post office or package delivery service to weigh them: they’re required to have accurate and frequently calibrated scales. Measure (or read-off) the length of your crank. You're going to hang these weights from your pedal axle so it helps if you raise the bike a bit: I put a dumb trainer on a sturdy desk, and drag a table near to it. The bike is clamped into the trainer and the front wheel is placed on the table so the crank and pedals (and hanging weights) can be positioned in-between the desk and table. "Zero" the torque reading, then hang the weights using strong cord or wire from your pedal axle, as near as possible to the face of the crank (this is to minimize “twisting” torque). Rotate the rear wheel backward until the crank is horizontal. When the crank is horizontal, the reported force or torque will attain a maximal value. Typically, it takes a few seconds for the reported value to settle down, so rotate the rear wheel slowly.

Multiply the mass by the crank length (in meters) and by the gravitational constant (roughly, 9.8 m/sec^2). For example, if you hung 25 kg of weights from the pedal spindle and the crank length was 170mm (= 0.17m), then an accurate power meter should report 25 * 9.8 * 0.17 = 41.65 Newton-meters. (If you have a hub-based power meter, multiply by the gear ratio). The difference between the calculated expected value and what was observed is a measurement of inaccuracy.

The test described here is also known as "The Stomp Test." As a rough validity check, you can do a less precise test just to see if the power meter and head unit are properly communicating. For this rough test, place the bicycle so that the front wheel is pointed into a corner of your garage or basement, and the bike itself is close to parallel to the wall. Arrange the crank to be horizontal, and stand with all your weight on one pedal. It can help to steady yourself against the wall with the backs of your fingernails so you're not supporting any weight with your hand. Pointing the front wheel into the corner keeps the bike from rolling forward. Calculate the expected torque as above, and compare with the reported value. This is not as precise as the method above because you tend to “bounce” a little on the pedal.

The longer answer

Although conceptually simple, modern on-bike power meters are operationally complex because they must work under a wide range of environmental conditions. Accordingly, they have many modes of failure that can lead to inaccuracy. Most (but not all) power meters use strain gauges (or strain gages) to measure force or load, and there are several failure points that can affect a strain gage's readings. The static torque test described above is a good starting point, but sometimes accuracy issues are more complex and in that case you may have to identify where a power meter could go wrong. If a power meter fails the static test it will always fail a dynamic test, but in some cases a power meter can pass the static test and still not provide high fidelity data under dynamic conditions.

In order to give a full answer, it will be necessary to describe how some power meters work and their points of vulnerability so you can devise tests to determine accuracy. Although it's possible for consumers to test their devices, some of these tests are more onerous and time-consuming that others; and not all uses for power meters require accuracy or precision.

How the manufacturers do it

Most manufacturers perform some version of a dynamic test, where they check the power meter on a dynamic rig like a dynamometer. The pedal, crank, or bottom bracket is clamped into a motorized rig that turns at a known rate with a known load, and reported power is checked across a wide spectrum of loads and rates. As we will see below, it is possible to replicate some of these same conditions at home.

Torque zeroing and slope calibration

Strain gages are thin strips of metal; when twisted or deformed under strain, their electrical conductance changes. They have a baseline resistance in unstrained state, but their conductance can also change depending on temperature and how well they are “anchored” to the underlying part (such as a crank arm, a crank spider, or a hub torque tube). Many years ago an entire generation of power meters produced by a well-known brand was plagued by a poor epoxy contact between the strain gages and the supporting component. Although the epoxy was fine when new, over time the epoxy “softened” and strain in the supporting component was poorly transmitted to the strain gage. Because on-bike power meters need to work under a wide variety of temperatures and shocks, they must be anchored well and they need to have some way to resist temperature changes that can expand or contract the supporting component. A common need is a way to set the baseline (i.e., to tare the gage) by “zeroing the torque.” Many head units confusingly call this “calibration.” In order to get the highest fidelity out of your power meter, you should not simply rely on the automatic temperature compensation, but also to manually “zero the torque.” Actual calibration is unique to each strain gage and power meter, and determines the relationship between strain deformation and electrical resistance. The resistance in properly installed and zeroed strain gages is designed to be linear over the range of operating conditions so the relationship between resistance and force can be summarized by a “slope:” this much change in resistance is linearly related to that much deformation which is caused by this other amount of load or force. The calibration slope of some, but not all, power meters is adjustable by the end user; in others, you can check to see if the calibration slope has changed but you cannot adjust it yourself. If the slope has changed for these models, you would need to send it back to the manufacturer for adjustment or replacement.

Rotational speed tests

Since a watt is a Newton-meter per second, and Newton-meters can be measured by the strain gages, the next part that must be measured is how long it takes for a crank to make a revolution; that’s the “per second” part. Many older power meters used reed switches to measure rotational speed: as a magnet attached to a crank arm passed, the switch would close and a sensor would record the time interval between closings of the switch. This is a very reliable technology but can’t tell the position of the crank arm between closings of the switch, only the time interval between successive closings. Many newer power meters use accelerometers rather than magnets and reed switches, and this has introduced both the ability to “know” where the crank arm is positioned anywhere around the unit circle, and also a newer potential source of error: the accelerometers must reliably infer the position of the crank, when it has returned to the same position, and the time interval between the start and end of a completed revolution. At the moment I know of no power meter with a “belt and suspenders” approach, combining accelerometers and reed switches.

Since all power meters and head units report speed and cadence, you can check the data fidelity of the reported cadence (and thus, time interval for a revolution) if you have a reliable source for speed. Whilst actively pedaling rather than coasting, a bicycle’s speed is determined by cadence and gear ratio. For geared bikes like those with separate cogs and derailleur systems, gear ratios are discrete. You can therefore calculate “estimated” gear ratios given speed and reported cadence. If the cadence and speed are accurate, the estimated gear ratios will fall into discrete buckets centered on the actual gear ratios determined by the chain ring and cog.

Typically, power meters suffer inaccuracy at cadences both very low (say, under 20 or 30 rpm) and very high (over 180 or so rpm), but also at more normal cadences when running over very rough terrain because the accelerometer signals become noisier. During mountain biking cadences can be quite low and torque loads quite high which, when combined with shocks from terrain, make MTB power measurements particularly susceptible to error.

Dynamic tests

In this bicycles.stackexchange question and answer, a dynamic method was discussed to estimate drag on a bicycle. As it happens, this method was originally developed to evaluate the accuracy of power meters – drag estimation was a secondary result. That said, it turns out that this method is very sensitive to accuracy in power measurement: power meters with poor accuracy produce estimates with high mean squared error. The test procedure is then similar to the dynamic calibration rigs used by manufacturers: you can ride at various powers and cadences, up and down hills, at high speed and low; the estimated drag and its standard error are then measurements of accuracy and precision.

In addition, although the most common power meters use strain gages, there are a handful of less common devices that use other technologies to measure power. In the absence of strain gages, the power meter cannot be checked with a static test. In these cases, a dynamic test may be the only way to check its accuracy.

Single-sided power meters

Single-sided power meters are a special case. Even if they do capture the correct crank torque and cadence, human beings are typically not bilaterally symmetric in their ability to produce power. Thus, even if they perform well on a calibration rig, they suffer from an additional source of error: changing asymmetry with cadence, force, or fatigue. In general, I have not had nearly as much success using data collected from single-sided power meters to estimate drag.

What to do about discrepancies?

If you've done either the static torque test or a dynamic test and found a discrepancy, the first question to ask is how much of a discrepancy matters to you. It is possible to train well even with an inaccurate power meter, as long as what you're doing is simple. Riders trained for a century before the advent of relatively inexpensive power meters.

However, if you do need accuracy in your power data (and some riders do) then you will need to identify whether the inaccuracy is due to an error in torque zeroing, slope calibration, timing, or because of asymmetry in your pedal stroke. Furthermore, you will have to identify whether the issue is transient (like, a weak battery that needs replacement) or more severe and consequential. Sometimes there are design flaws in the power meter -- an example is the recent revelations about the right side instrumented Shimano cranks. In those cases, you will have to contact the manufacturer.