Given that most modern aircraft are controlled using the fly by wire system, what is the likelihood or the drawbacks of transmitting those fly by wire instructions from the cockpit and or cockpit computer wirelessly? Wires add weight to the aircraft and hence increase the net fuel burn. I'm assuming a totally wireless system is not already in use today.

- 71,714

- 21

- 214

- 410

- 8,529

- 12

- 57

- 111

-

5and risk loss of communication? – Federico Sep 15 '17 at 11:54

-

4A fly-by-wireless then...? The question is not so clear, because wireless sensors, wireless feedback, and wireless avionics are already in sight. Do you mean wireless control of actuators? Note: Control of actuators doesn't account so much in wire weight, especially when hydraulics powered actuators are used. But the ratio will increase in "more electric" aircraft. – mins Sep 15 '17 at 13:30

-

1There's a short paper from NASA on this subject: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/20070013704.pdf – Johnny Sep 15 '17 at 16:08

-

4I tried but failed to find the User Friendly cartoon where passengers take control of the plane with their laptop wifi... – Dronz Sep 15 '17 at 19:09

-

2I think you've overlooked something: most if not all of those devices will still require wires in order to provide power. If the weight and/or cost of separate control wires is an issue, it's certainly possible to multiplex the data & control signals over the power wires. – jamesqf Sep 16 '17 at 04:25

-

A very detailed inventory of WAIC on the ITU site (Report M.2283): Technical characteristics and spectrum requirements of Wireless Avionics Intra-Communications systems to support their safe operation – mins Sep 17 '17 at 10:47

-

There are reseach projects underway close to this area, one example is SHAWN > https://scc.rhul.ac.uk/research-projects/ – jrtapsell Sep 17 '17 at 14:35

8 Answers

The fly-by-wire is absolutely vital for control of the aircraft, and the three dominating factors here are safety, safety and safety. Weight is not one of them. The fly-by-wire system is triple or quad redundant: instead of removing a set of cables, the manufacturers are installing 3 more cable looms, just to make sure that the system always works.

Wires are safer than wireless!. There are active transmitters and receivers in wireless systems, which can fail. Signal reception depends on the quality of the space between transmitter & receiver: can the signal always penetrate the aluminium bulkhead? What happens to the wireless signal when flying past airport radar or in the weather radar field of another aircraft?

Shielded wires are passive and relatively immune to electro-magnetic radiation, and are the means of choice for such a safety critical system.

Update

The OP was on fly-by-wire. In a sense, the flight control system is the most safety critical system on board and must be immediately available at all times. The presentation linked to by @mins in a comment reports on the progress of on-board wireless communication, for systems with a less critical safety aspect:

Examples of Potential WAIC Applications

Low Data Rate, Interior Applications (LI):

- Sensors: Cabin Pressure - Smoke Detection - Fuel Tank/Line – Proximity Temperature - EMI Incident Detection - Structural Health Monitoring - Humidity/Corrosion Detection

- Controls: Emergency Lighting - Cabin Functions

Low Data Rate, Outside Applications (LO):

- Sensors: Ice Detection - Landing Gear Position Feedback - Brake Temperature - Tire Pressure - Wheel Speed - Steering Feedback - Flight Controls Position Feedback - Door Sensors Engine Sensors - Structural Sensors

High Data Rate, Interior Applications (HI):

- Sensors: Air Data - Engine Prognostic - Flight Deck/Cabin Crew Images/Video

- Comm.: Avionics Communications Bus - FADEC Aircraft Interface - Flight Deck/Cabin Crew Audio / Video (safety-related)

High Data Rate, Outside Applications (HO):

- Sensors: Structural Health Monitoring

- Controls: Active Vibration Control

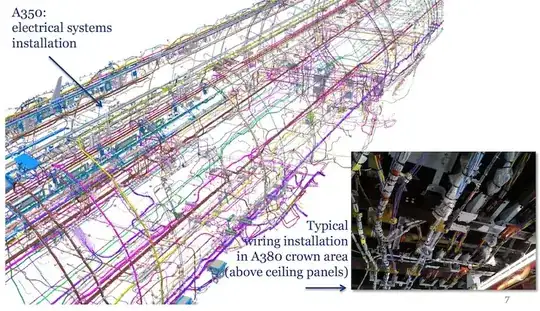

From the same presentation: An A380 has 5,700 kg of wires on board, and 30% of them are potential candidates for a wireless substitute. So wireless communication on board of aircraft does make sense, starting with the non-safety critical systems first.

- 61,680

- 11

- 169

- 289

-

10"Wires are safer than wireless", until they are broken. Wire + wireless may be safer (page 10) than 2 wires. – mins Sep 15 '17 at 13:16

-

7@mins Yes everything can break. Does one have a higher chance of breakage than the other, is the question. Wireless does not even have to break to be rendered inoperative by external radiation. – Koyovis Sep 15 '17 at 13:19

-

3@mins Flight control cables can break, hydraulic lines can break, the electrical wires carrying power to the actuators can break, etc. If the wire with the signal to the actuator breaks, is the wire with the power for the actuator still there? Sounds like the solution would be redundant & physically separated sets of control and power wires, rather than a jammable wireless control that still needs power at the actuator. – Ralph J Sep 15 '17 at 14:19

-

3@RalphJ: What the presentation linked explains is that when all redundant wires have no other possibility than being close together (e.g. in the wing), wireless offers another choice ("Route segregation, combined with redundant radio links, provides dissimilar redundancy and mitigates risk of single points of failure". The key point is this is a mix wire+wireless, not wireless alone. And of course it's not for power, but for weak signals. – mins Sep 15 '17 at 14:54

-

3System failure aside, a wireless system would be incredibly trivial to jam. – reirab Sep 15 '17 at 15:13

-

"incredibly trivial to jam": Not from the inside of a Faraday cage, should the communication occurs outside of the cage. That would indeed be the case. – mins Sep 15 '17 at 15:14

-

1@mins what makes you think the jammer would not be inside the cage... – Trevor_G Sep 15 '17 at 15:22

-

2

-

6What @reirab said. If you can control your aircraft wirelessly, so can someone else. Or at least, they can certainly block your ability to control the craft. Which for a malicious actor is all they really need to do. And no, an aircraft is not an effective Faraday cage. If it was, you wouldn't get so many people yakking away on their cell phones the moment the plane touches down. – aroth Sep 15 '17 at 15:40

-

1@mins Yeah, aroth is right. Aircraft aren't that great of Faraday cages. There's enough attenuation that GPS signals don't work well (since those signals are barely above the background noise anyway,) but not enough to even significantly affect a cell phone, let alone a jammer. For that matter, I've connected to the Wi-Fi in a lounge from inside a plane sitting at the gate a few times before. Also, the avionics would be inside the fuselage, too, though the flight control surfaces are obviously outside it. – reirab Sep 15 '17 at 15:49

-

@aroth: Aircraft wireless is moving on, as I wrote at the top of this page, wireless sensors, wireless feedback, and wireless avionics are already in sight. I didn't mention rudder or ailerons actuation. A band has been secured by the WRC/ITU (4/5 GHz that is today used for radio-altimeters, but will be vacated). Indeed there are challenges, but industry is already spending money on tests, regulation and standards. The big driver is sensors are gong to be in astronomic quantities in future aircraft, and wires can't be used. – mins Sep 15 '17 at 20:06

-

@reirab: Yes windows offer this possibility, but windows can also be made to stop the 4/5 GHz band if needed. Then please also consider that wire jamming is also possible (this is the official reason behind turning off PED), but jamming devices can also be detected and neutralized easily. – mins Sep 15 '17 at 20:21

-

@mins Sensors, feedback and avionics are one thing, and may not be bad. Parts that make the airplane go different places are entirely different. Wireless is incredibly trivial to interfere with. Lnafziger is absolutely on the right track. Lightning is worrisome. Also, if you add in the needed encryption + validity and redundancy checks, I'd imagine the latency of a wireless signal will be significantly greater than a wire. Even a tiny fraction of a second is more latency than I want. I'd be less comfortable with a fly-by-wireless aircraft than with a remote-controlled, pilotless aircraft. – Shawn Sep 15 '17 at 20:21

-

RE your update, yes but as I pointed out in my answer, you can so the same with single wire communication and distributed controllers/computers without all the issues and risks of radio communication. A method the naval industry has been using for a couple of decades to reduce the millions of feet of cables that needed to be run through modern warships. – Trevor_G Sep 16 '17 at 12:32

-

Your addition on WAIC shows the major revolution that is happening in aerospace regarding wires. There are 2 very detailed documents for those who are interested in details: ITU report M.2283, and this full presentation used in 2015 for a workshop (the first was an extract only). – mins Sep 17 '17 at 11:04

That will be very unlikely simply because wireless is much less reliable by several order of magnitude.

considering the current day an age of terror threats if the encryption (and you will need encryption) is ever compromised this would allow a passenger to hack into the datastream and Man in the Middle the controls for a hijack without ever entering the cockpit.

You also have not considered the power requirement of the wireless communication, that will also increase fuel cost.

To save a few hundred kilograms of weight this is never going to happen.

- 27,428

- 5

- 79

- 143

-

2Never going to happen? Well the goal of the AVSI is to save 30% of the wire weight using radio ("About 30% of electrical wires are potential candidates for a wireless substitute!"). – mins Sep 15 '17 at 13:37

-

3@mins that presentation doesn't aim to replace the aviation control wires, (which is what the question is about) – ratchet freak Sep 15 '17 at 14:13

-

8Just thoroughly jamming the signal would be enough -- hacking to take control would be "nice" from an attacker's standpoint, but jamming the frequency and thus all the controls would be entirely sufficient to bring down the aircraft. – Ralph J Sep 15 '17 at 14:15

-

1No need to crack the encryption. A jammer would take down a "fly-by-wireless" system with ease and they're pretty trivial to make. Just broadcast a bunch of white noise in the right band and that's it. – reirab Sep 15 '17 at 15:10

-

Quantum entanglement may be unhackable and unbreakable. I would define it as wireless. – Christiaan Westerbeek Sep 17 '17 at 10:00

-

@ChristiaanWesterbeek : unless its software implementation has bugs. Practically uncrackable encryption already exists (which would need billions of years to brute-force even if every atom in the universe was a computer), but they do occasionally get hacked due to bugs in their implementation. – vsz Sep 17 '17 at 13:01

-

The problem is not that encryption could get hacked, but that the control center could be hacked. Is it easier for 500 people to storm an aircraft in the air and break into the cockpit, or to storm a control room running servers on the ground that send commands remotely? – forest Jun 23 '19 at 06:11

-

@reirab You can design a wireless protocol to be nearly immune to jamming attacks if it's heavily spread-spectrum. The term for this is LPI (Low Probability of Interception). You can use FHSS+DSSS with OFDM and frequency hopping. These are all common technologies used to reduce interference, but can be easily modified for anti-jamming purposes. Sending out an ultra wide-band white noise generator would use an obscene amount of power (an impractical amount). – forest Jun 23 '19 at 06:13

Although technically feasible, having wireless communication between cockpit and the various end-points around the aircraft produces significant issues.

Primarily:

Channels: Unless you use multiple frequencies, each sensor or driver would need it's own radio channel. Add in redundancy and you need like three channels per sensor or actuator station.

Bandwidth: Wireless communication is limited in how much data you can transfer at a time. Since you would be sharing the channels over multiple devices, this further limits how fast you can communicate with it.

Interferance: Assuming you can even get all these devices working at the same time, you are very susceptible to electrical noise. Whether that be Timmy using his little game-boy, or dad using his electric razor in the washroom, or travelling through an electrical storm, a sudden loss of communications in any form would be detrimental to the passenger and crews flight experience.

Security, Hacking / Blocking: It would be rather too easy for a would be terrorist to turn on a transmitter to block the wifi or hi-jack the control system.

As such, wireless communication would be a rather dangerous road to venture down.

As for harnesses. When it comes to control systems, harnesses can be significantly reduced by using a different method. By using distributed smart controllers located around the aircraft, a single wire communication system can be used to connect them to the main flight computers. That is, you really don't need a wire in a harness for every switch in the cockpit.

As always, there needs to be redundancy here, you design it with two or three communication cables routed through the roof, floor etc. for redundancy in case one fails or is severed. You would still need a power distribution system of course.

However, the issue with all these methods is that of channelling too many functions through a single point. Although it may be a simpler system and more reliable, the consequences of a failure are far more significant.

- 4,876

- 2

- 24

- 36

-

3What do you mean with "unless you use multiple frequ., each [...] own radio channel"? Classic radio channels actually use multiple frequencies. Mind you that today we can choose from many other multiple access techniques including time division and spread spectrum. Likewise, wireless bandwidth may be very high. There is really no shortage in terms of channels and bandwidth for the requirements of flight controls. – bogl Sep 15 '17 at 15:18

-

@bogl yes bandwidth and channels go hand in hand here. You either use a lot of channels with limited time division or less channels and a lot of time division. Either way,, it's problematic for real time control. – Trevor_G Sep 15 '17 at 15:20

-

3Do you really need a different channel for every item? Similarly to how you can have multiple transmitters on a bus, or multiple cell phones on the same frequency, you don't need a different channel for each transmitter. You can use time multiplexing, code-division multiplexing, or even space-time coding if you're ambitious, I'm not sure how deterministic real-time behavior can be guaranteed for these, but real-time wireless networks do exist. – Cody P Sep 15 '17 at 17:34

-

In my opinion, the most important issue would be that of immunity towards the interference to wireless signals (from the FCS to the actuators) from external sources or impact of environmental factors on the transmission of the signals - what is the reliability of the wireless signal transmission in all the imaginable situations. Until we have a technology which eliminates these issues the industry would be very sceptical of use of wireless FCS. As of today, the next thing coming up in FCS is Fly-by-Light i.e. signal transmission using fibre optics. There are a number of pros of FBL over conventional FBW such as high speed, immunity to EM interference etc, but at the same time it may not be significantly lighters than copper wires as a over-all system which could trigger the switch to FBL in civil domain for example.

- 918

- 6

- 10

-

Fibre optics is indeed a good and relatively immune way of point-to-point communication. The trouble with it though is that it is difficult to implement in a databus setup, hard to splice a signal into an existing wire. Hub-and-spoke architectures grow exponentially with number of sensors, and there are more & more in modern aircraft. – Koyovis Sep 15 '17 at 21:11

-

Fiberoptics also tend to have the problem that they don't deal very well with being jerked about. This isn't really much of a problem on the ground, but in an aircraft that can be subjected to fairly strong turbulence, that's an issue that you need to keep in mind. Admittedly, it can be overcome, but by that point one has to start asking what you're gaining by using fiberoptics over copper in the first place. Also, as long as the computers are electronic, don't forget that at some point you'll have to have some kind of device bridging the electrical/light gap, at best introducing only latency. – user Oct 22 '17 at 11:37

No.

While wireless communication could help to reduce the number of cables, the remote control units and remote terminals still require cabling for power.

Advantages of wireless systems include mobility and flexibility. These could be driving factors for some early prototypes, but clearly not for certified airliners. The side effect of harness reduction is not significant.

Thus, doing with less wires is possible, but wireless is not.

- 731

- 4

- 12

There are several pros and cons to the system, and several great links to existing research have been provided by others here. Manufacturers like Gulfstream and Boeing have prototyped some examples of wireless avionics and it's an area of active research with plenty of papers proposing different strategies. So I wouldn't go so far as to say that fly-by-wireless is unworkable or a horrible idea, although it's telling that it hasn't been widely deployed yet in other industries for in-vehicle networks to my knowledge. Like many ideas posted here, it has its merits but the benefits may not be enough to overcome the challenges.

Pros to wireless control:

- Less cabling weight, maybe by as much as over a thousand kilograms

- Reduced engineering cost for harness design, cable routing, and shielding

- No wires that you have to shield from electrical interference (instead you have an antenna picking up interference)

- Fewer issues due to broken connectors, snapped wires, transmission line effects from faulty terminations, etc.

Cons:

- Increased engineering cost in wireless transmitters

- Increased complexity (think of how Wi-Fi has more connection issues than LAN)

- Greater chance of single-point-of-failure issues. Aircraft have several redundant buses routed through different points in the aircraft. It's easier to jam or take out all wireless communications than all these redundant wires.

- You need to use a secure architecture with encryption and authentication signatures because you no longer have a guarantee that intruders aren't on the data bus. The military already uses similar technology in a variety of radio applications.

- Extra security software and hardware to detect network intruders, prevent dangerous interference, etc.

- Impossible to completely protect from jamming, even if using military-grade anti-jamming techniques like spread spectrum and frequency hopping.

As an interesting point related to hacking, most modern flight control computers are immune to nasty Byzantine General errors. These errors are situations where one of several sensors or control computers fails and misleads the others, including even lying to one and telling the truth to another. Even in these situations, the system is designed to detect the liar and still reach full and correct agreement between the functioning computers. To take down these systems you'd have to impersonate two, or sometimes even three, flight control computers or servos at once.

Also, many systems are designed to prevent hardover. For example, the if the rudder is detected to deflect fully, the avionics might revert to a simpler backup control system (which is possibly mechanical). These systems can be circumvented with the right techniques of course, but to imply that its trivial for one system to go rogue and take down the whole plane is like implying a bridge will fail if you cut one support beam. You shouldn't ignore the extensive safety analysis and redundancy that goes into these designs.

- 6,773

- 2

- 26

- 55

-

The expression fly-by-wire is reserved for the flight controls, to distinguish them from fly-by-cable, just mechanically deflecting a valve or the control surface directly. There is research budget spent on wireless technology for aircraft, for systems with low safety impact. Not the flying controls. – Koyovis Sep 19 '17 at 05:20

-

@Koyovis If you read the Gulfstream link I posted, it talks about a prototype with "application of wireless signaling for a primary flight-control surface". So it appears there is research on wireless technology for flying controls. – Cody P Sep 19 '17 at 06:50

-

1" A mechanical system controlled the ailerons; a Fly-By-Wire system manipulated the outboard spoilers; the Fly-By-Wireless system handled the mid-spoilers; and a fiber-optic Fly-By-Light system moved the inboard spoilers." Interesting research. Primary control still done mechanically. – Koyovis Sep 19 '17 at 07:29

Wires are far more resistant to electromagnetic interference, either intentional or situational, than radio signals.

Also, transmitting radio signals to remote receivers that are encased in either aluminum or carbon fiber would pose some difficulties. One could use the aluminum skin of the aircraft as an antenna, but that would be supplying a great antenna for external radio signals, too, and you have a potential interference issue again, one that could be applied external to the aircraft.

A more practical approach has been to replace metal wires with fiber optics. Fiber optics have a higher speed and much wider bandwidth that can carry multiple signals per strand, as well as weighing a lot less.

Some years ago, the Lockheed C130 was redesigned with a fiber optic based system. The result removed so much wire and weight from the cockpit area that the previously optional cockpit armor became standard, to keep the plane in balance when it had no cargo.

- 8,767

- 1

- 23

- 37

Something I haven't seen any other answer touch on is this: Wireless transmitters require wires to power them. Instead of running a wire from cockpit to system, you're running a wire from the planes power grid to the transmitter, then another wire to the receiver.

Congratulations, by not using wires, you've doubled the number of wires.

- 131

- 3

-

The wired transceiver would have also required power. Assuming 2 signal, power, and ground, you halve the number of wires. But power may be routed differently than data. – Eric Johnson Sep 15 '17 at 20:26

-

The goal is not to reduce the number of wires, but their length/weight. And most wireless devices won't need to be powered from the aircraft, that's the element which allows to move on. Devices can have batteries or other sources of energy like induction on RFID. – mins Sep 15 '17 at 20:32

-

@mins How long are these batteries going to last? How will you replace them when they're low? How much of a weight savings do you expect to gain when you're adding all these batteries? How do sensitive avionics in the aircraft deal with the entire airframe being bathed in magnetic flux from induction chargers? – UIDAlexD Sep 15 '17 at 20:48

-

@UIDAlexD: "How will you replace them when they're low?" The batteries on my home smoke detectors last 10 year and that's not rocket science. Many solutions exist. E.g. I'll have a single battery for 50 sensors and I'll charge it during maintenance, on the ground. If I use an induction method, the inductor will stay on the ground. – mins Sep 15 '17 at 21:42

-

Except in the rare cases of two-wire passive sensors, or one-wire signaling for hydraulic acutators most flight control computers, servos, and actuators already have power going to them, so you haven't "doubled the number of wires". – Cody P Sep 18 '17 at 16:10