All rotor heads need to deal with multiple forces but two in particular have a big influence on the design and complexity of the rotor head.

As a blade moves forward (the advancing blade), it experiences an airflow equal to the speed of the blade plus the air speed. As the blade moves backwards (the retreating blade), it experiences an airflow equal to the air speed minus the speed of the blade.

Therefore, the advancing blade generates more lift and will rise which causes the airflow to hit the blade with a more vertical component, reducing the angle of attack and the lift generated. The opposite happens to the retreating blade.

This causes the advancing blade to flap up and the retreating blade to flap down. The rotor head must allow this to happen and deal with the resulting forces.

The second effect arises from the Coriolis effect. This results in a force applied to the hub by each blade as it speeds up and down called lead/lag.

There are three main types of rotor head.

Fully articulated.

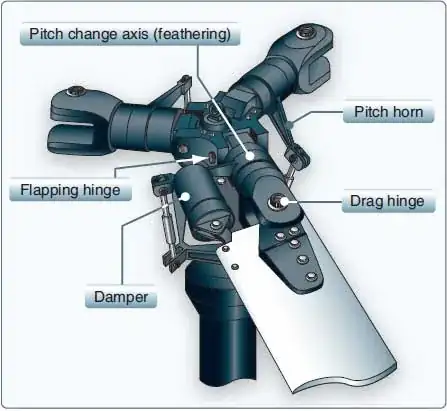

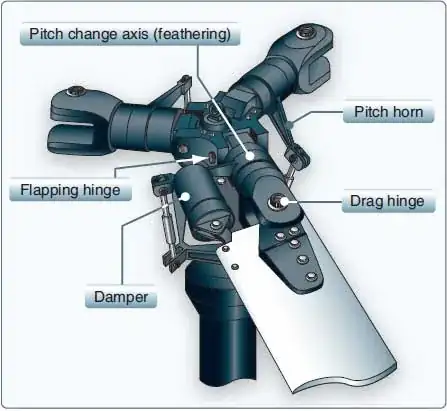

From danubewings.com, copyright of FlightLearning.com

The blades are attached to the hub with hinges that allow the blade to flap up and down and lead/lag (or drag) hinges around the hub, allowing these forces to be absorbed without applying them to the blade or the hub. The blades may also rotate in a cuff through which the blade is attached to the hub. Each blade can flap and lead/lag. Note that dampers may also be fitted to reduce vibrations and to better absorb the forces.

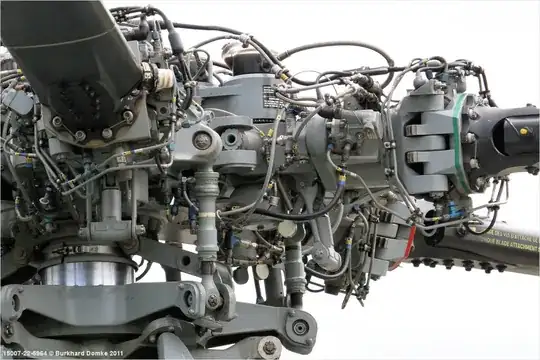

These are the most complex heads, an example of which is in your first image.

Semi-rigid.

Copyright www.copters.com

The blades are attached to the head with lead/lag hinges only. Flapping is enabled by allowing the entire head to "teeter" on hub so that if one blades rises, the other must fall. They cannot flap independently. Since the entire disc tilts together, semi-rigid heads can only have 2 blades.

The coning hinges allow both blades to move up and down together, without regard to where the teetering hinge is, as power is changed collectively. So, the flapping (or teetering) hinge enables cyclic flapping whilst the coning hinge enables collective flapping.

Rigid.

Copyright helistart.com

The blades are rigidly attached to the hub and the flapping and lead/lag forces are absorbed entirely through flexing of the blades. This is the simplest of all heads.

The choice of rotor head type is a complex one with intended design and performance being primary drivers but, as the head gets more complex, rigid being the simplest and fully articulated being the most complex, the maintenance cost goes up and generally, so does the weight. Conversely, fully articulate heads produce the lightest loads on the main rotor shaft, it's thrust bearings and the gearbox coupling allowing weight savings to be made there. Rigid heads also require the strongest blades, and therefore weight, although modern composites are enabling the manufacture of blades with high flexibility but lower weight.

The head you have shown is particularly complex as it is six bladed and has an automatic folding system so that it can be stored and hangared in small spaces and be ground manoeuvrable on aircraft carriers with limited deck space. The tail folds at the same time as the blades. Most of the stuff you can see apart from the blades, their cuffs and their hinges is hydraulic piping, pumps and motors, electrical bonding strips, sensors and transducers. There is also an oil lubrication system for the bearings - you can see the oil reservoir on the top of the hub. The use of elastomers in bearings has removed a lot of the need for lubrication.

If you stripped all of that it away, it wouldn't look (quite) so complex. I.e. Not so barking mad!

Copyright helistart.com